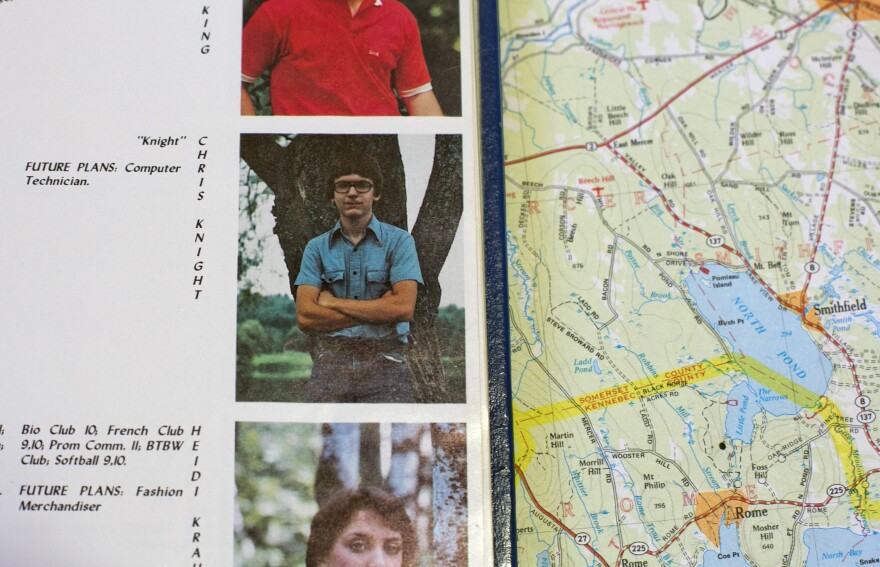

Unless you’re a hermit yourself, there’s a good chance you know about Chris Knight, better known as the North Pond Hermit. Knight lived alone in the woods in the Belgrade Lakes area for 27 years, stealing the necessities of life from camps before he was discovered and arrested in 2013.

His story attracted tremendous attention, both positive and negative, from media all over the world. For some he was a folk hero; for others, he was a thief who made them feel unsafe and unsettled; and for still others, he was an object of pity.

For writer Michael Finkel, who saw the story in the Kennebec Journal, one thing stuck out: Over his two and a half decades outdoors, Knight stole thousands of books.

Knight refused to speak to reporters after his arrest. But when Finkel wrote him a letter, he responded, and the two ended up writing back and forth about books and meeting several times during, and then once after, his time in jail.

Finkel’s new book on Knight is “The Stranger in the Woods.”

Finkel: There were as many opinions about Knight as there were people. I spoke to at least 40 families that owned cabins around North Pond, and the opinions ranged from complete understanding, if not jealousy, to the completely other end of the spectrum where people hid in the dark with their weapons drawn, ready to capture this guy, and wanted him once he was captured to spend the rest of his life in jail, because he’d broken into their house. And none of those opinions are wrong.

Nora Flaherty: There was it seems a profound feeling of unease in these areas, because people thought they were going crazy, they didn’t know if this was real or fake. And it seems like after he was arrested, people were almost giddy.

Finkel: It’s almost impossible to overstate how long this legend sort of built up. They named this thing, this character, this person, they didn’t know what. There were about 200 cabins around North and Little North Ponds, and for years — decades — there’d been these mysterious break-ins, and people were baffled. Some people thought they were losing their minds, maybe they forgot to buy batteries, maybe they didn’t put the steak in the fridge. There was nobody who thought there could be a person who lived in the woods all this time.

And so, it was sort of like this legend, in the book I compare it to the Loch Ness Monster, or the Yeti, just this mysterious thing, and once Knight was captured, rather than people feeling — I mean there was this sense of relief that their houses would no longer be broken into — but really the overwhelming sentiment was further disbelief that this legend was real.

It would be like the Loch Ness monster just decides one day to stroll out of Loch Ness, and there really was a monster there. People were more startled by the truth than they were by this myth.

Flaherty: What do we actually know about Knight with regard to a mental or psychiatric condition?

Finkel: He was examined by a state psychologist, who determined that he possibly has one of three syndromes: Asperger’s, depression or schizoid personality disorder.

But really there is no perfect fit for a diagnosis. In fact, it seemed that — and I don’t want to hit anyone too hard with this — but really, the more time I spent with Knight, I would leave my conversation with him and immediately turn on my phone and be inundated with noise. There was a hint that it wasn’t Knight who was a little crazy, it was possibly the rest of us.

Flaherty: You mentioned the thing that sort of got you about this is that he collected books, and he read so much. I’d guess you’re not the only one who had a “thing” that made them fascinated by this guy. What other things did people tell you about?

Finkel: Everybody had a different point of disbelief. How is it this man didn’t freeze to death? How is it possible that he could go 27 years without seeing a doctor? How could he go 27 years without speaking to someone, and suddenly his voice works perfectly fine, he doesn’t have any lack of vocabulary? But he answered all those questions, in a way that made complete sense, and there’s not a shred of evidence that he didn’t do what he said — in fact, almost everyone who’s met him, including the police officers who arrested him, found him not only to be honest but almost incapable of lying.

Flaherty: You were let go from the New York Times for publishing a story that wasn’t truthful — you used a composite character. With this story, you are the only journalist that Knight talked to, and much of what’s in the book is based on conversations between the two of you. How did you prepare to be challenged on this?

Finkel: It was essential to me not only because of my history as a journalist, but also because this story demands it, to be as factually accurate as possible. I was allowed to take notes when I interviewed Knight, and I hired not one but two professional fact checkers. Now, I’m human, it’s possible there’s a mistake in here, but this story, to the best of my abilities, is completely true.

Want more hermit? Michael Finkel will appear on Maine Calling this coming Tuesday. And the documentary film, “The Hermit,” will air this month as part of Maine Public Television’s community films series.