Gambling developer Shawn Scott’s campaign to convince Mainers to approve a casino at an undisclosed location in York County began nearly two years ago with over $20,000 in refunds for bus tickets, airfare, rental cars and hotel rooms.

The travel reimbursements went to the first wave of petition circulators deployed to public squares and Walmart parking lots across the state. The circulators, hailing from Oregon, California, Texas, Florida and elsewhere, were lured by the promise of up to $10 for each signature they helped collect to get the casino proposal on the Nov. 2016 ballot.

Complaints soon surfaced about circulators’ aggressive and deceptive tactics. One of them, John Merchant of Florida, was stopped by Augusta police in the small lot next to the Maine Department of Secretary of State — the same office that would later rule that more half of the 91,000 signatures gathered by the campaign were invalid because of widespread irregularities, a determination that blocked the proposal from the 2016 ballot.

Merchant was given a trespass warning after he entered the offices of the lobbying firm Capitol Insights and demanded payment for his services.

The episode signaled the turbulence that has followed the casino campaign at seemingly every turn.

After two years, over $6 million spent and amid an ongoing investigation by the Maine Ethics Commission into the campaign’s finances, Scott’s casino proposal will appear as Question 1 on Nov. 7.

An unorthodox campaign, scrutinized

At the moment, the York casino campaign resembles the gambling initiatives that preceded it, including the proposals in Oxford and Bangor voters approved in 2010 and 2003, respectively.

Like previous proposals, the York County campaign has commissioned an economic analysis projecting thousands of new jobs and a deluge of tax revenue to the state.

It’s also launched an expensive television ad campaign that focuses less on the proposal’s gambling operation and more on the potential for a resortlike facility — a facility that is neither mentioned nor required in the legislation voters will consider in November.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4zyZy2z3Ww

But Scott’s campaign is arguably more audacious than the casino proposals Mainers have previously considered, and far more controversial. Its aggressive tactics, big spending and secrecy have spurred calls from state lawmakers to overhaul Maine’s citizen initiative process.

After state election officials ruled more than half of its petition signatures were invalid in 2016, the campaign dumped another $1 million to get the signatures it needed. All told, the campaign spent over $4 million just to get the proposal on the ballot — a staggering, if not unprecedented, amount for a Maine ballot campaign.

Since then the Ethics Commission has subpoenaed bank records and other documents to help determine whether the campaign obscured its funding sources for over a year. It’s unclear whether the ethics investigation will be completed before Mainers go to the polls Nov. 7, but the campaign’s well-documented tactics — and Scott’s checkered past — could still influence voters.

The opposition campaign is counting on it. A Bad Deal for Maine, linked to the Churchill Downs owners of the Oxford Casino, which could directly compete with a York County casino, last week launched the website wickedshady.com. It highlights the trail of litigation and licensing problems left by Scott and his associates.

Proposal tailored for Scott

The legislation voters will consider on Election Day was criticized from the start.

The first page of the five-page bill makes it clear that only Scott, or a company that he controls, can hold the license for the York County casino.

Scott first brought gambling to Maine when his campaign successfully convinced Bangor voters to approve slots at a race track there in 2003. He later obtained a racino license, but not before the Maine Harness Racing Commission accused him and his business associates of operating a web of shell companies and “sloppy, if not irresponsible financial management.”

The report also revealed Scott and his associates were involved in over two-dozen lawsuits over an eight-year period.

The trail of litigation has followed Scott and his associates ever since he sold the Bangor facility to Penn National in 2004, netting a reported $51 million. And two years ago, the government of Laos seized a gambling facility run by Scott’s Bridge Capital firm following charges of corruption.

The proposal also exempts the casino from the law that prohibits new gambling operations from locating within 100 miles of an existing gambling facility. The law was passed so that casino facilities don’t cannibalize one another.

If passed by voters, Scott’s casino would be in direct competition with Oxford Casino, which is why it’s drawing opposition from Churchill Downs.

Funding network revealed

Until April, Scott’s role in the financing of the campaign was suspected but not known. His sister, Miami resident Lisa Scott, appeared as the only donor to the campaign. But that changed after an unusual public hearing on the proposal by the Legislature’s Veterans and Legal Affairs Committee.

During the March hearing, Dan Riley, an Augusta lobbyist hastily retained by entities backing the campaign, told the committee that he had been hired by Bridge Capital, a high-risk investment firm based in Saipan of the Mariana Islands, in which Scott is a partner.

Riley later said he was mistaken about the identity of his client. Nonetheless, his testimony prompted the Ethics Commission to question the casino campaign about its funding sources.

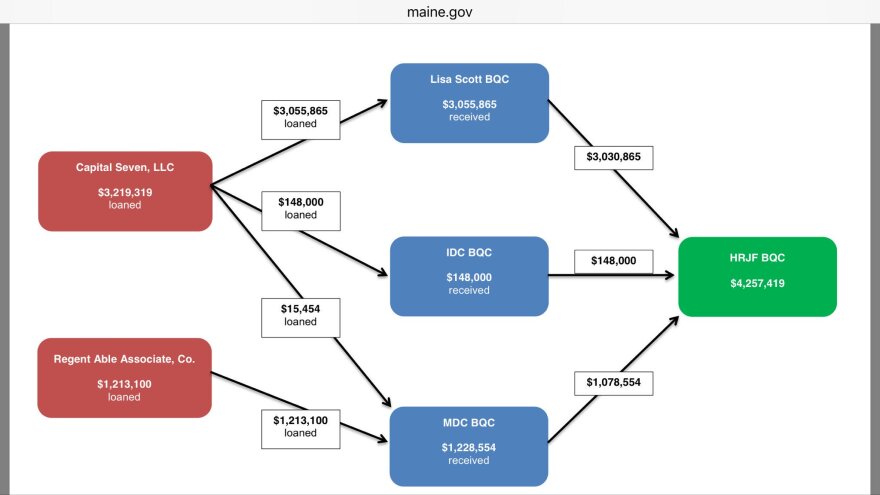

In April, the campaign filed a new round of finance reports, revealing domestic and offshore funding sources with ties to Shawn Scott.

A similar network of corporations was involved in the campaign to pass gambling facility in Massachusetts last year. The campaign ran afoul of regulators there for hiding Bridge Capital’s involvement, and was fined $125,000.

The Maine campaign faces the potential of a much steeper fine — $4 million — an amount equal to the contributions it failed to disclose on time.

The campaign pivots

Over the summer, the casino operation began transitioning to a more conventional campaign. And like the signature gathering effort, it has spared no expense.

The political action committee Progress for Maine hired several high-profile consultants, including Goddard Gunster, the D.C.-based firm that helped convince British voters last year to leave the European Union.

Progress for Maine has paid Goddard Gunster over $574,000 according to the latest campaign finance reports. It also paid $100,000 to Andrew Ketterer, a former Maine Attorney General hired by the campaign to represent its interests in the ethics investigation. Ketterer also acted as public advocate for the project, holding a series of press interviews last week that appeared designed to give the campaign a much needed boost in legitimacy.

After Ketterer left the attorney general’s office in 2000, he served on the Maine Ethics Commission, the very same agency that’s investigating the casino campaign.

Progress for Maine is also targeting its opposition, Bad Deal for Maine and media outlets that have scrutinized the campaign. It’s unclear whether those attacks will have the desired effect, especially for a campaign that has generated so much scrutiny since it launched nearly two years ago.

Nonetheless, pass or fail, the casino proposal could spur changes to the referendum process and the state’s patchwork gambling policy that inspired it.

Maine Public Morning Edition host Irwin Gratz: The vote next month on the York County casino may be about campaign tactics and business practices as much as it is about slot machines and blackjack tables. Steve Mistler has been following this odyssey and gives a full accounting at Mainepublic.org. Steve joins us now with the abridged version.

Gratz: Hi Steve. The backers of this wanted this vote held last year. Why wasn't it?

Mistler: Well they had a really short window to collect the 61,000 plus signatures that they needed to get on the ballot in 2016. The campaign has never really divulged this but you can assume by the way they acted that they thought they could close that gap by increasing the amount of money they were paying to paid circulators to get these signatures that they needed. They were paying up to $10 per signature, which is a lot of money. It's a staggering amount of money in this business. But what happened was, once the circulators went out to collect the signatures, there were reports that they were overly aggressive or they weren't being fully honest about what the proposal was. And, so, at the end of the day, they gathered about 91,000 signatures and submitted those to the secretary of state to validate them. And less than half of them turned out to be valid. Then, the secretary of state issued a report saying there were these widespread irregularities. And that, in effect, blocked the proposal from appearing on the 2016 ballot.

Gratz: How expensive has this total effort been and where is all this money coming from?

Mistler: Well, it's a great question. I mean, it's been very expensive. They've spent $6.1 million so far. And to put that into perspective, the same-sex marriage campaign from 2009, which had actually repealed Maine's same-sex marriage law at the time - that was four-and-a-half million, and that was very expensive for a Maine referendum. So, $6.1 million so far, and over $4 million was spent just to get on the ballot. And that is the staggering part of this - that doesn't even count for the advertising and everything else that's taking place right now. So that $6.1 million figure is going to go up. There's no question about it.

You asked where that money is coming from. Up until April we thought it was coming from Lisa Scott, who is the sister of the person who would benefit from this proposal - the only person who could actually hold a license for this proposal - which would be Shawn Scott. But in April we discovered that at least Scott wasn't the funder of this campaign. She was basically a pass-through agent for a network of domestic and offshore companies that have been funneling money through her into this campaign committee.

Gratz: Now you mentioned Shawn Scott. His name has been linked to this. Who is he and why does his involvement in this matter?

Mistler: Shawn Scott - he should be familiar to some Mainers. He brought gambling to Maine in 2003 when he introduced a referendum in Bangor that would allow a race track there to have slot machines. He was successful in that effort, but he also made headlines by trying to get the license for that operation because there was a harness racing commission report that looked into his finances, his business associates, and the report that they came out with was not flattering to Shawn Scott. There were widespread questions about his business interests and a trail of litigation that has continued ever since 2003. After that report came out, Shawn Scott sold the license to the Bangor facility, netting himself $51 million. And there's some concern that that's what his aim on this proposal is to do as well, which is to get voter approval and then turn around and flip the license to somebody else who would run the facility.

Gratz: So what exactly is the state Ethics Commission looking into and when might we expect its findings?

Mistler: Well the Ethics Commission is investigating the finances of this operation. The true funding sources for this campaign were obscured for over a year, and I think the Ethics Commission is trying to find out: (a) do we know whether or not all of the funding sources have been revealed, and (b) whether or not the campaign hid those funding sources intentionally. And if they do find that out, and they assessed the late penalty, this casino operation could be hit with a significant fine - $4 million, that's the extent that it could be. It could be also be less than that. That will be up to the Ethics Commission to make that determination. Whether or not that happens before Election Day is unclear. There is an Ethics Commission meeting that's scheduled for the end of the month. I don't know that they're going to get to the bottom of their investigation by that time.

Gratz: Steve, thanks very much.

Mistler: Thanks Irwin.