The oldest among us are getting older. According to the 2010 Census, nearly 2 million people were age 90 or above, and that number is expected to quadruple by 2050. It’s among the fastest growing segments of the population.

At one independent living community in Portland, there are so many nonagenarians that they’ve formed a club called the Nine Decades group.

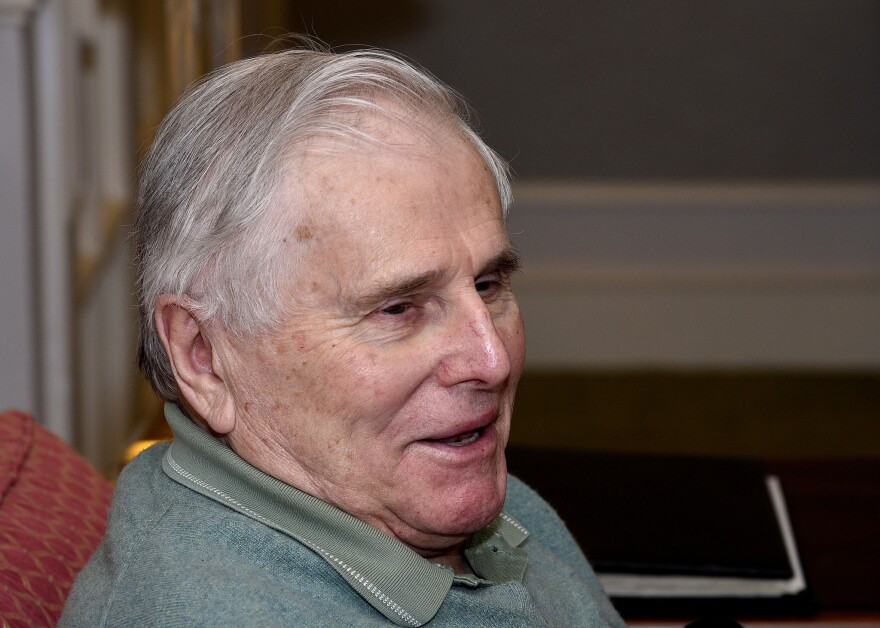

This is the first part of our series “In This Life,” which focuses on older Mainers.

If you want to find the Nine Decades group, head over to The Cedars retirement community in Portland on the first Monday of the month, and listen for laughter.

Twenty-four of the residents seated in a circle for a recent meeting are age 90 and above. And they love to joke about age.

“The first time I felt old was when my daughter went on Medicare,” says member Bob Ryan.

The members of the club, which formed last year, have a common bond, says Paul Korpela: They’ve achieved something that many never expected.

“It’s a bunch of us that wonder about each other, to a certain extent, as to, at 90, how come you’re still here?” he says.

The members of the Nine Decades group have outlived friends. Some have outlived spouses and even some of their children. As they navigate their ninth decade, Les Brewer, the group’s current leader, says they’re in search of a larger mission.

Brewer encourages members to submit their DNA to a data bank to help answer questions about longevity. He also suggests that the group create a how-to guide for younger people.

“So we can teach ‘em how to come along and attain the age of 90. So please think of how you’ve done it, how you would suggest other people might follow and do it,” he says.

“I don’t know, probably good Scotch, good life,” says Elaine Adams, 91. She just moved into The Cedars about a year ago. “Well, I’ve had a positive attitude, I don’t worry about much. Never have. I just go with the flow.”

“Attitude. You have to have the correct attitude,” Korpela says. “You avoid depression, and there’s quite a bit of it around here. But you avoid it by socializing with people. And it’s much easier at our age to socialize with people your own age.”

“I’d like it better if it was a mixed community of all ages, because I miss seeing the little ones,” says Harriet Bogdonoff, 94.

Bogdonoff thinks genetics play a role in her longevity because her mom lived to be 92. Attitude is also important, she says. But that doesn’t mean she gladly accepts whatever comes her way.

“That’s a hard one. Because it’s taken me a long time to accept my limitations,” Bogdonoff says, attempting to describe this stage of life compared to other stages.

To be sure, she keeps very busy. She takes classes at a local university, swims and does yoga. But she has had to give some things up. She uses a walker now, and recently decided that she can’t travel anymore. That means she can’t visit her lifelong friends she left behind in New Jersey. But, she says, you have to move on.

“It’s a matter of accepting one’s limitations gracefully and still appreciating what life has to offer. And that’s what I tell myself every day,” she says.

Along with physical changes, these 90-somethings say they also contend with changes in their relationships. Even from well-meaning family members, Korpela says.

“They get very protective of you, and start reverting back to a childhood kind of thing. ‘Dad, don’t get up. I’ll get your water for you. Don’t get up. I‘ll get the paper for you,” he says. “And I should be getting up. You should get up and move every hour.”

“You’re old, and sometimes they don’t want to listen because you’re just plain old. ‘Oh Nana, I don’t want to hear that,’” Adams says.

But the passage of time has also helped to strengthen family relationships. Bogdonoff moved here to be physically closer to her daughter, but now they’re closer in other respects.

“Closer in how we think about one another, and how we like the same things, and how we can relate to one another as equals. That’s special,” she says.

Bogdonoff has already had to say goodbye to her husband and one of her daughters. The losses are painful, she says, but death is a part of life.

“Well, my father died when I was 12. So that was a hard one for me. But I was introduced to death early on because of that. But I had no feeling of being immortal. And I knew that when my time was up, it would be up, and I’m ready to join my husband,” she says.

“You have to realize why you’re here. To put it bluntly, we came here to die,” Korpela says.

“I put that in the background. I lived. As long as I could live, I never thought of dying,” Adams says.

“Well, I’m curious. I’m more curious than anything else. I mean, what’s it like? Who was it, the Apple guy that just died” Steve Jobs. They claim that as he was going, he all of a sudden says, ‘Wow.’ And I’m very curious as to why he said, ‘Wow,’” Korpela says.

“Well, we know it’s going to happen,” Brewer says with a chuckle. “It happens to everybody. And I think the biggest problem for me, having lived as long as I have, you just can’t pick the time or pick the way it will happen.”

That’s seems to be the biggest worry. Not dying itself, but the potential for mental or physical deterioration. Still, Brewer, Adams, Bogdonoff and Korpela choose not to dwell on it.

“I don’t feel there’s any bad parts of living in your 90s. In my particular case, there’s always an opportunity to do something either for the community or for others that I get the most satisfaction from,” Brewer says.

“Truthfully, and to be honest, aging does stink. But what can you do? You’re going to be here. You’re lucky to be here if you’re in good health, and that’s something to feel lucky and proud about. I’m proud to have reached 91,” Adams says.

“I’m lucky to be alive.” Bogdonoff says.

“I feel wonderful. I’m having a blast. I’m one of those happy ones. Attitude. That’s the secret. That’s always the secret. Regardless of how old you are,” Korpela says.

“In This Life” is made possible by a grant from the Doree Taylor Charitable Foundation.